The Hidden Benchmark of Economic Growth: A Primer to Understanding Total Factor Productivity

While many aspects of America’s economic health are discussed at length in the public arena, total factor productivity (TFP) is often overlooked. Yet exploring TFP can be crucial to understanding an economy’s vigor — and its future.

Defining Total Factor Productivity

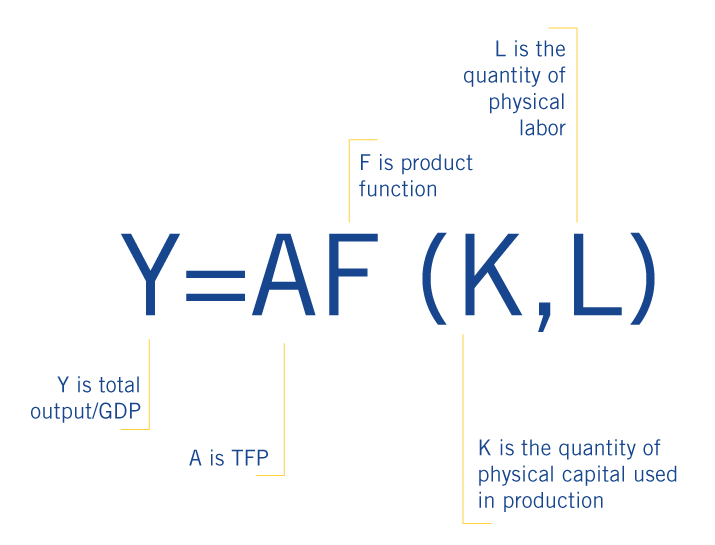

Found in the equation for determining the gross domestic product (GDP), TFP can be defined as “the portion of output not explained by the amount of inputs used in production,” according to Harvard Business School professor Diego Comin. Mathematically, it is represented by A in the Solow model for measuring GDP:

Where Y is the output (or GDP), K is the quantity of physical capital used in production, F is the product function (a dynamic number) and L is the quantity of labor.

In his interview with the Freakonomics podcast, renowned economist Robert Gordon clarifies:

“[TFP] tells us how much progress our economy is making, relative to the hours of work that we put in and relative to the number of machines that we use. And so improvements in efficiency per unit of labor and per unit of machine is called total factor productivity. And you might just translate that into simple words: the impact of innovation.”

Although “the impact of innovation” may not seem like a significant economic driver, it has real importance, helping economists understand the dynamics of the economy over time.

Historical Context of American Economic Growth

To understand the significance of the current total factor productivity, it is helpful to contextualize the total factor productivity in history.

The Industrial Revolution

One of the most significant periods of technological advancement occurred between the years 1860-1900. Also known as the Industrial Revolution, this period of time produced unprecedented technology that substantially altered the way humans live their lives.

Gordon explains that the total factor productivity was high during this time because the inventions created were 1.) numerous, 2.) radical, and 3.) impacted a wide range of areas of daily living.

The Industrial Revolution was incredibly significant in terms of innovation, Gordon explains in an article from the Journal of Economic Perspectives. He proposes that advancements in technology came in five great “clusters.”

- Electricity

- The internal combustion engine

- Advancements in “rearranging molecules” (such as the invention of plastics and pharmaceuticals)

- Entertainment/communications/information

- Running water

Notable revolutionary inventions that stem from these technologies include the electric light, the personal automobile, motor and air transport, the telegraph, the phonograph, radio, motion pictures, television and the flush toilet.

Gordon explains that the total factor productivity was high during this time because the inventions created were 1.) numerous, 2.) radical, and 3.) impacted a wide range of areas of daily living. Electricity decentralized sources of power and made it possible for tools and machines to become portable. It also gave rise to consumer appliances, thus freeing up time (e.g., laundry machines), eliminating food waste (refrigerators) and increasing economic development in the American South (air conditioners).

The internal combustion engine gave way to developments such as the suburbs, highways and supermarkets. It also helped reduce or eliminate rural isolation. Those items that “rearranged molecules” diminished air pollution and eliminated or reduced common sicknesses. The entertainment cluster transformed communication and art. And running water brought indoor plumbing and urban sanitation.

All this, Gordon states, resulted in an increase in per capita income that lasted well into the 20th century.

The Great Depression

However, it is also commonly known that the Great Depression disrupted America’s economic growth. The total factor productivity also fell about 18 percent, to one of its lowest points during that time. The specific reason for its downturn remains, ironically, a mystery.

Economics professor Lee E. Ohanian presents a possible explanation for why this may be so.

He suggests that the reason for such a significant drop in TFP may have been a “decrease in organizational capital.” In other words, there was a breakdown in the organizations that allowed capital to move, such as in supplier and customer relationships. This could have led to reduced efficiency in technology use.

The Current and Future State of the American TFP

After the Great Depression, total factor productivity continued to rise, but by a small margin. Robert Shackleton, the principal analyst at the Congressional Budget Office, suggests that this may have been the “full final exploitation” of the progress made during the Industrial Revolution.

While computers are speeding up and becoming more refined, they no longer have the overhauling effect on daily life they once did.

The American TFP began to slow down substantially in the mid-2000s, a phenomenon that continues to this day. According to the International Monetary Fund, many believe this is due to the “fading positive impact” of the IT revolution. While computers are speeding up and becoming more refined, they no longer have the overhauling effect on daily life they once did. But a slowing tech industry is not the only culprit for lowering total factor productivity.

TFP growth, the IMF claims, depends on other factors besides technological advances. These include the extent to which businesses are able to innovate and operate in environments that foster competition, their ability to provide modern efficient infrastructure and an economy that allows easy access to finance. While technological change has been stable, technological efficiency has slowed.

Current stagnation of the total factor productivity naturally leads to the question: What is the future outlook for the American TFP? While no one can definitively say, two strong, opposing arguments have emerged on the world stage.

Innovation researcher Erik Brynjolfsson, however, believes that the current economic stagnation is temporary. In his TED Talk, he argues that America’s lack of growth is only a “growing pain” for what he calls the “New Machine Age.”

Gordon believes that America’s robust economic growth may soon be coming to an end. Growth, he says, was at its highest from the 1930s to 1950s, then began to decline. Soon the growth rate will return to one that is comparable to others in human history before the Industrial Revolution. Furthermore, any economic growth the United States may encounter will be stunted by four systemic problems he calls “headwinds.” These include an aging workforce, a broken education system, pervasive economic inequality and the drying up of Social Security benefits.

Innovation researcher Erik Brynjolfsson, however, believes that the current economic stagnation is temporary. In his TED Talk, he argues that America’s lack of growth is only a “growing pain” for what he calls the “New Machine Age.” This age, he says, is defined by ideas and brainpower, which is much harder to track with old tools of economic measurement but is every bit as valuable.

It’s difficult to measure the worth of this new era, he claims, because so many goods and services are exchanged for free (around $300 billion worth, by his calculations). The greatest issue in successful advancement is what he calls a “great decoupling”: Productivity numbers are high, but so are those for unemployment. The key to economic improvement, therefore, is to integrate the efforts of people and technology together.

Gaining Greater Insight Into Economic Factors

Whatever the health of the TFP, understanding productivity is crucial to gaining insight into the trajectory of economic progress. At Concordia University Texas’ online MBA program, students can learn the economic theories and the skills needed to implement them in order to become leaders of industry. Courses are eight weeks long, providing students with an accelerated path to obtain their degree.